A unique reenactment of a Greek hoplite (rather a general or commander) by the Spanish historical association and reenactment group Athena Promakhos (copyright: Athenea Promakhos /Denis F.). Kudos to them for their fine work on the topic of ancient Hellenic warfare.

Hoplite military equipment

31/03/2022

Uncategorized Ancient Greece, Ancient warfare, Greek warfare, helmet, Hoplite, hoplite phalanx, hoplite warfare, Military, Military history, Military technology, Sparta Leave a comment

THE HOPLITE SHIELDS

11/10/2017

Uncategorized Ancient warfare, Athenians, Athens, Boeotia, Greece, Greeks, Herodotus, Hoplite, hoplite phalanx, hoplite warfare, Military topics, Shield, Sparta, Spartans 7 Comments

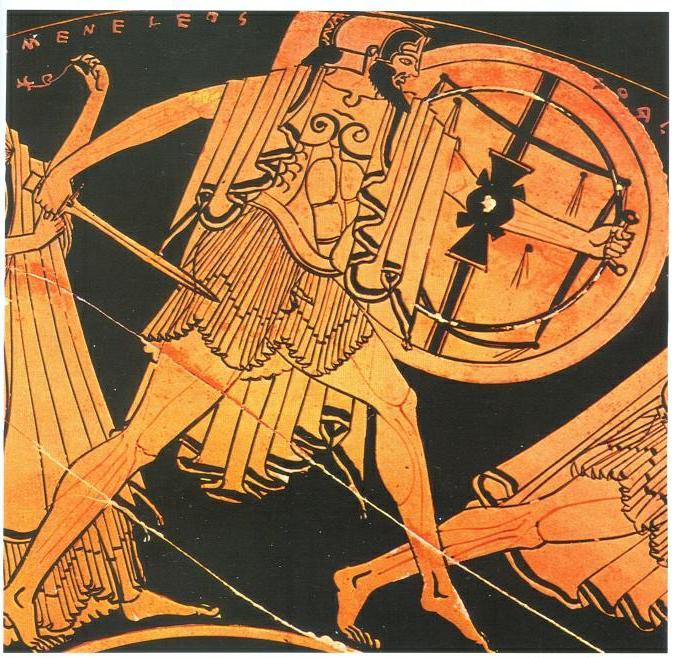

A vase painting depicting a hoplite, 5th century BC. He is armed with a bronze cuirass, a hoplite sword and a hoplite shield of the Argive type. In the interior of the hoplite shield, you can see the “antilave” («αντιλαβή», handle/handgrip), the “porpax” («πόρπαξ», fastener for the elbow) and the “telamons” («τελαμώνες», shoulder belts)/ (Paris, Louvre Museum)

–

By Periklis Deligiannis

.

The Geometric Period (11th-8th centuries BC) preceded the invention of the hoplite warfare and the hoplite phalanx (about 700 BC). The shields of the Geometric period belonged to two main types: the “Dipylon” type shield and the “Herzsprung” type. The Dipylon shield is named after the Athenian Dipylon gate, where a number of pottery with depictions of that type of shield, was discovered. It was a large and long shield, covering the warrior from chin to knees. It was made of wicker and leather, without excluding further strengthening of wooden parts. Despite its size, the Dipylon shield was light due to its materials. It had a curved form in order to embrace the warrior’s body. In the middle of its surface, the Dipylon shield had two semicircular notches for the easier handling of the offensive weapons (spear or sword). Notches also facilitated the hanging (suspension) of the Dipylon shield on the warrior’s back, in order not to restrict his elbows when he walked. The shield had at least one central handle for its holding by the warrior in battle, and one or more shoulder belts, in order to hang it on his back when not used. These belts were called “telamones” (τελαμώνες). The shape of the Dipylon shield denotes its origins from the famous Minoan and Mycenaean eight-shaped shield. During the Greek Archaic Era (7th cent – 479 BC), the Dipylon shield was made mostly of bronze and had a smaller size: that is the “Boeotian” type of shield, named after Boeotia, where it was popular.

LEONIDAS’ LUCKLESS BROTHER: DORIEUS THE SPARTAN

15/01/2016

Uncategorized Ancient warfare, Cleomenes, Cyrenaean, Cyrene, Greece, Greek, Hoplite, hoplite formation, hoplite phalanx, Leonidas, Libya, Military topics, Sparta, Spartan Leave a comment

.

By the end of the sixth century BC, Anaxandridas of the Agiad royal family, one of the two Spartan kings (Sparta had two kings), had a difficulty in bearing children from his first wife. The Spartan ephors forced him to take a second wife – despite the southern Greek monogamy – in order to obtain a successor. Anaxandridas’ second wife gave birth to Cleomenes, who was destined to become one of the most skilful Spartan kings. However, shortly after the birth of Cleomenes, Anaxandridas’ first wife also gave birth to a son, named Dorieus. Although Dorieus came from the king’s first wife, Cleomenes succeeded Anaxandridas to the throne as firstborn. Dorieus became furious because of the takeover of royal power by Cleomenes. Thus he decided to organize a colonization campaign, in order to leave forever Sparta (515 BC). His first choice for the founding of his colony, was the site of the river Kinyps in Libya. The men who followed him out were referred by the sources as “Lacedaemonians” and it seems that they included a few real Spartans (Spartan citizens, called omoioi). The Spartan omoioi followers of Dorieus were mainly his personal friends and some members of his political faction. The majority were other Lacedaemonians, mainly hypomeiones (fallen citizens, ex-Spartans who were just beginning to become numerous), perioikoi (free Lakonian, Messenian and Pylian subjects of Sparta) and Peloponnesian allies.

A SMALL SPARTA FAR AWAY FROM GREECE: THE LIPARIAN ISLES

27/08/2014

Uncategorized Aeolian Islands, Carthage, Greek colonization, hoplite phalanx, Italy, Lipari, Military history, naval history, Naval warfare, Phoenicians, Rhodes, Sicily, Syracuse 2 Comments

By Periklis Deligiannis

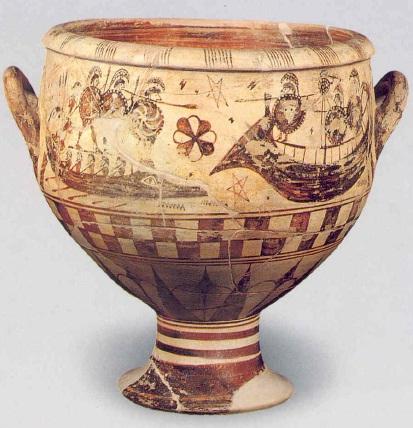

The renowned “Aristonothos vase” (about 700-650 BC) manufactured in Magna Graecia by Aristonothos and discovered in Caere of Etruria (Etruscan Caisra). Its vase-painting of a naval battle (image below) provides us with a very good representation of the ships used by the Greek and the Etruscan sea-fighters (almost identical), and of naval warfare during the acme of the Aeolidae Islands (Archaic period).

–

The Aeolidae (Aeolian) or Liparae (Liparian) Isles is a cluster of small islands in Sicily, northwest of the Straits of Messina. In this article I will deal with an unknown aspect of their history which is related with a very interesting episode of the ancient Greek colonization.

In Sicily, around 580 BC, the Selinuntian Greek colonists finally resigned from claiming disputed lands from their Geloan brethren (in which lands, Acragas was founded) in exchange for aid by Dorian settlers coming from Rhodes and the Anatolian Greek colony Cnidos (Knidos), who arrived in western Sicily through Gela. Pentathlos, the leader of the Rhodian and Cnidian colonists, was a Cnidian like most of his men.

The Selinuntians used the Cnidian and Rhodian reinforcements in their ongoing war against the Elymians and the Phoenicians. They helped them to establish a new Greek colony at Cape Lilybaion (Latin Lilybaeum), just 10 kilometers south of Motya. They were trying to establish a new Doric power against Motya (the main Punic colony on the island) and Carthage, while they would deal with the subjugation of the Elymian Segesta which resisted stubbornly their expansion. The Selinuntians, Cnidians and Rhodians joined forces against the Elymi, Sicilian-Phoenicians and Carthaginians.

Diodorus Siculus states that the main battle between the two blocs took place near Lilybaeum, obviously in the hinterland between Selinus (Selinunte) and Segesta. Pentathlos was killed; the Greeks were defeated (580/576 BC) and immediately after, the Elymi and the Carthaginians attacked Lilybaion and drove off from there the Cnidians and Rhodians.

THE BATTLE OF CUMAE, ITALY (524 BC)

04/06/2014

Uncategorized Ancient warfare, battle of Cumae, Capua, Cumae, Etruscan, Greek, Herculaneum, hoplite phalanx, hoplites, Italy, Magna Graecia, Naples, Oscans, Pompei 2 Comments

Italian lightly armed warrior (by Peter Connolly), the main type of lightly armed Italian warriors who attacked Cumae in 524 BC. Especially for the peoples of the Apennines, the central mountain range of the Italian peninsula, this was the main combatant type. These hardy and stubborn warriors, mainly Oscan and Southern Umbrian, caused great problems in Rome in the coming centuries. The depicted warrior has a native Italian helmet with a Greek-type plume. He bears a protection plate on his neck and a pactorale – a circular disk to protect his chest. He holds two spears – one heavier and one lighter. He also has a Greek-type sword (copyright: Peter Connolly).

.

By Periklis Deligiannis

.

In 745 BC, the Euboean Greek settlers who had colonized years ago, the small island Pithekousai off coast of the Bay of Naples in Italy, founded Cumae (Cyme in Greek, Cumae in Latin) on the opposite coast. Cumae was the first ‘official’ Greek colony in the Italian peninsula. Pithekousai was actually the first, but ‘unofficial’ colony in Italy. Cumae took its name from the Euboean Cyme, rather as a neutral compromise between Chalkidean and Eretrian settlers, the most numerous among the Euboeans. Chalkis and Eretria were the most powerful city-states of the large island Euboea in the Aegean Sea.

Soon Cumae, enhanced by new colonists from Chalcis, Eretria, the Euboean Cyme, Tanagra (Boeotia), Cirinthos (Euboea) and Oropia (Boeotia), expanded in the fertile land of the Phlegraian Fields to the north. Later, further more Greek colonists arrived in Cumae from Magna Graecia, Samos etc. founding subsidiary colonies and thereby increasing the extent of the Cumaean territory. Among the Cumaean colonies, Neapolis (modern Naples) would become the most important. In other cases, the Greeks settled in existing villages o f the indigenous Ausones, turning them into Greek colonies, as it happened in Pompeii, Heraklion (Herculaneum), etc. Thus the boundaries of the Cumaean territory were approaching fast the river Volturnus, but soon they were confined by a powerful enemy: the Etruscans (or Tyrrhenians as the Greeks used to call them), the people of Etruria (modern Tuscany), mostly of Anatolian origins (from Lydia, Asia Minor).

The competition between the Greeks and the Etruscans was older enough. The mythographer Palaifatos (“On Unbelievers”) assures that the sea monster Scylla, which Odysseus encountered on his wanderings (“Odyssey”), represented the danger facing the Greek merchant ships in the Strait of Messina, from the Etruscan pirates.