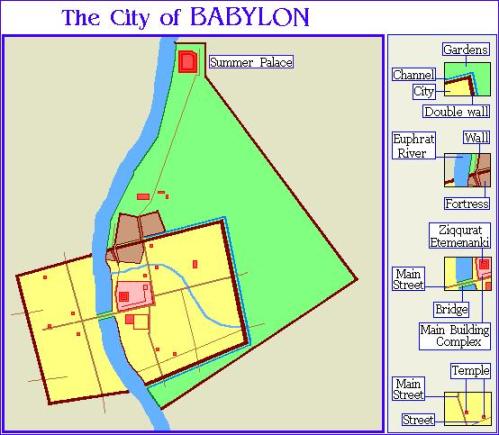

Α diagram of Babylon in Nebuchadnezzar’s reign.

.

By Periklis Deligiannis

.

Babylon was one of the most splendid and renowned cities in world History, being a real metropolis of the Near East and the political centre of a large kingdom and occasionally an empire which lasted more than a thousand years (18th-6th centuries BC), sometimes under foreign dynasties. The Babylonian kingdom remained nominally an independent political entity even when it was conquered by invaders such as the Kassites (Kossaioi) or the Assyrians. Even after Babylon’s capture by the Persians, she remained a very important city under the rule of the Achaemenids, of Alexander the Great who had chosen her as his capital, and of the Seleucids. Babylon’s gradual decline starts in the Late Seleucid and the Parthian Age and goes on more densely during the Sassanid Persian period.

The first appearance of Babylon in the historical-archaeological records possibly belongs to the 23th century BC, as a town of the Akkadian kingdom. However it is possible that the town pre-existed as a Sumerian settlement. Its inhabitants at that time seem to have been Akkadian Semite newcomers who had already started to replace the Sumerians as the main population of South Mesopotamia. I believe that a part of Babylon’s original population was Sumerian. In this phase, there is no urban planning and Babylon was in fact a Sumerian-type village or town because of the strong cultural influence of the indigenous people on the Akkadians (some scholars believe that the Akkadians were also indigenous of southern Mesopotamia, but I do not share this view).

A representation of the city of Babylon; view from the Gate of Ishtar. Note in the front level the double wall of the inner defensive system, and the heavy fortifications of the Gate of Ishtar (painted blue). In the deeper level, note the Etemenanki Ziggurat and behind it, the Esagila (Temple of Marduk).

.

The early town was established on the east bank of the Euphrates River and it was rather of small importance compared to the neighbouring great cities of Kish, Nippur, Akkad, Eshnunna and Sippar, all of them Sumerian except Akkad.

Around the 20th-19th centuries BC, the infiltration and occasionally invasion of the Amorites to Lower Mesopotamia was the fact that changed Babylon’s fortunes and started her evolution to an important city and then to a metropolis. They probably came mainly from the modern Syrian semi-desert areas, thus being a people of the Northwestern Semitic group, and were Bedouin-type nomadic tribes. However they gradually established themselves as upper classes and dynasties in many of the old Sumerian and Akkadian cities of the land. They initially infiltrated small towns like Babylon: indeed, the town is growing in this phase, probably due to the arrival of the Amorites who are added to the earlier inhabitants. However Babylon still cannot be compared to the neighbouring cities.

Around 1895 BC, Babylon became the political centre of an Amorite dynasty who overthrew the control of the neighbouring city-state Kazalu. Babylon became an independent but small city-state and remained in this status until it became the capital of the great Amorite king Hammurabi, the founder of the Early Babylonian Empire. During his reign, Babylon became the largest city in the world, overshadowing her aforementioned neighbouring cities which had been conquered by Hammurabi. After his death, the Amorite dynasty remained in power in Babylon; however the city became again a city-state and due to this situation, lost a part of its population which could not be supported.

The reconstructed Ishtar Gate at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin (Wikipedia).

.

In 1595 BC Babylon was captured by the Hittites in a ‘Blitzkrieg’ operation of them against her. The city was looted and possibly partly destroyed, consequently loosing an additional part of its population.

It was then that the Kassites (later Cossaeans), an Indoeuropean or perhaps Hurrian people of the Zagros Mountain Ridge found the opportunity capturing the city and holding it for more than four centuries. The Kassites secured peace for Babylon which again started to grow in population. Additionally, the Kassites were partly Babylonized but around 1150 BC they were ousted from the city due to the Assyrian and Elamite military pressure.

In the 11th century BC new Semitic nomadic peoples, the Arameans and Sutians, infiltrated Lower Mesopotamia and the former managed to control Babylon for a while. They were finally absorbed and lost their rule but remained there as a part of the population. The next two centuries another Semitic nomadic population entered the region, the Chaldeans who annexed some areas of the Babylonian territory. As it will be mentioned below, they too will become a significant part of Babylon’s multiethnic population. Due to those arrivals that increased the population, and the economic growth of the city, at the early 1st millennium BC there was a new urban and at the same time architectural growth of Babylon. But then this situation was abruptly stopped by the city’s total destruction in 689 BC by the revengeful Assyrian king Sennacherib. However this destruction although possibly reduced the population, it also benefited the city architecturally because the new Assyrian king Esarhaddon rebuilt it at once in order to avoid the revenge of Marduk, Ishtar and the other Babylonian gods.

Due to the advance of the Assyro-Babylonian civilization and the ‘opportunity’ of the total destruction of the city, its urban planning was definitely improved and the architecture and embellishment of the temples and buildings were possibly improved as well. After all Esarhaddon made the city his capital, together with Nineveh.

Map of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

.

In the late 7th century, Babylon came under the rule of the Chaldean dynasty of Nabopalassar; the Chaldeans already being a significant part of her population. The Babylonians, Medes, Scythians and Persians managed to destroy the Assyrian Empire (between 612-606 BC), and Babylon became the political centre and metropolis of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

Nabopalassar started a new age of architectural activity for Babylon, but it was his son, Nebuchadnezzar II (Nabu-kudurri-usur II) (reign 604-562 BC but he was earlier co-regnant with his father) the one who led the city to the peak of her power and wealth. He ruled her and the Neo-Babylonian Empire for more than 42 years and provided Babylon with an advanced urban design and several magnificent buildings and constructions. He ordered the complete reconstruction of the imperial buildings, including the Great Ziggurat (E-temen-anki), and the construction of the Ishtar Gate (see below).

Military architecture also reached a high level in this new Babylon. According to the Greek historian Herodotus (Book I, 178-186) the city had the form of a gigantic square. Modern archaeologists estimated the maximum extent of its area to around 900 hectares or 2,200 acres.

This enormous for the ancient standards, area was protected by strong fortifications. The main protection was provided by a formidable defensive system which included a double defensive wall and a deep encircling moat. This system encircled the inhabited area on both banks of the Euphrates. The walls were made of unbaked bricks, according to the Mesopotamian standards.

The inner wall (of the double wall system) was more than 6 metres thick but its exact height is difficult to be estimated. It was interrupted by towers regularly located every 18 metres.

The inner wall was separated from the outer one by a space more than 7 metres large. The outer wall had a thickness of 3.5 metres and the towers on it were regularly located every 20 metres.

A representation of the ‘Old City’ of Babylon (view from the ‘New city’). Note in the front level the formidable double wall protecting the Great Ziggurat and the Temple of Marduk.

.

The defensive moat encircled the outer wall. Its bed was lined with burnt bricks and bitumen. The water in the moat was provided by the Euphrates through canals. It has been hypothesized that there was a number of bridges over the moat which could be moved off in an emergency.

The magnificent Ishtar Gate provided the ‘official’ entrance to the city. Despite the elegant view of this main gate, it was protected by a complicated system of defensive towers that made it look almost unconquerable. A reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate is located at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin and another one near the archaeological site of Babylon. The large Northern Fortress outside the double wall was protecting with its system of towers the road towards the gate. As it was generally common in the cities of ancient Near East, the towers had a major defensive role.

The Ishtar Gate seems to have been the most ‘official’ one but there were seven more gates, fortified at an analogous style. These eight great gates (including the Ishtar Gate) had massive doors covered with bronze.

The old city, on the east bank of the Euphrates, was protected by an additional outer fortification system. It has been estimated that Nebuchadnezzar decided its construction in order to protect the most important part of the city (‘Old Babylon’) but on the evidence of inhabitation inside this outer fortification system, I believe that he had estimated a further growth of the population, thereby he wanted to ensure a protected space for this future expansion of the city. There is a theory that the area protected by this additional outer fortification system was covered with gardens. I believe that there is not enough evidence for this view.

The additional outer fortification system comprised another double wall and perhaps a shallower moat without a bricked bed. It started from Euphrates’ east bank around 2,5 kilometres north of the Ishtar Gate where it was protecting the king’s Summer palace, ran in a direction to the south-east and then turned south-westwards to meet again the Euphrates, around 400 metres south of the inner fortification system.

Babylon’s defence had almost no aid from the geophysical status of the city’s site. The almost flat area of the site, despite some hilly ground, did not provide a strong geophysical obstacle in which the defence of the city could be based. Only the Euphrates could be used as a very strong defensive line for the Babylonians in order to protect one of the two parts of their city, if the other part had already been lost to the enemy. This lack of geophysical aid for Babylon’s defence was one of the reasons for her advanced military architecture.

The modern archaeological site of Babylon, together with a reconstructed part of her fortifications and buildings.

.

In conclusion, the fortification system of Babylon during Nebuchadnezzar’s reign was perhaps the most formidable of its time, equal to an imperial capital. An invading army would have to defeat the numerous and well trained Babylonian army in the open field, outside the outer fortification system, then capture the latter through bloody fighting, then capture the outer wall of the inner fortification system, and then conquer the inner wall of the same, through even more bloody fighting. But this would not be the end: the invaders would have to conquer every urban block through street fighting and also the smaller gates inside the city (but the latter never actually happened).

The canals of the city would also offer strong lines of defence, especially the old canal Libil-hegalla (meaning ‘May it bring welfare’ in Babylonian). The origin of this canal is sometimes attributed to Hammurabi twelve centuries ago, but it was Nebuchadnezzar who reconstructed it, lining its bed with burnt bricks and bitumen. Other canals brought prosperity to the gardens of the city on the west bank and to the suburbs on both sides of Euphrates, consisting at the same time defence lines against an invading army.

Α big disadvantage for Babylon’s defense was the lack of a high hill in which a citadel could be built, that wiould significantly strengthen the protection of the larger city. However in the flat area of Babylonia, the high hills are very rare. The lack of such a natural defensive obstacle which could be used as a powerful base for a counterattack against an invading army that had already conquered the lower city, is probably one of the main reasons of the eventual conquest of the city by several enemies.

Another diagram of the city of Babylon (source: imninalu.net)

.

Concerning the buildings and constructions inside the inhabited area of Babylon, they included mainly according to Herodotus the following. There were 100 smaller brass gates inside the city.

The main temples and sanctuaries included the magnificent E-temen-Anki Ziggurat, the Great Temple of Marduk (Esagila) and fifty two other temples including the ones of Ninmah, Ishtar in the ‘Old City’, Ishtar in the ‘New City’, Nabu, Ishhara, Ninurta, Enlil, Adad and Ea. Inside probably the Great Temple, there was the Golden eidolon of Baal and the Golden Table, both of them made of solid gold. There were also at least two golden lions and a gold human statue 5.5 meters high.

Herodotus mentions also another architectural construction of Nebuchadnezzar: the famous “Hanging Gardens”, being one of the ‘Seven wonders of the Ancient world’. But many researchers (including the writer of this article) believe that they were in fact in Nineveh, the Assyrian capital. Their mention as “Hanging Gardens” probably concerned that they were much elevated in comparison to the rest of the city (Nineveh). Some kind of Royal Gardens were also constructed as well in Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar being a standard construction for the Assyro-Babylonian kings but they were not the architectural success of Nineveh’s ‘Hanging Gardens’.

A representation of the heavy fortifications of the Gate of Ishtar. Note the complicated system of towers covering one another, and all together the royal gate. Note also in the front level the towers of the Northern Fortress outside the double wall, protecting the road towards the gate. Representation in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin (Wikipedia commons).

.

There were 180 altars to the goddess Ishtar sparse in Babylon. Her main streets were covered with stone slabs of around 1 square meter.

Nebuchadnezzar’s palace was a magnificent building according to the ancient tradition. This was rather the case, taking into account other palaces of Assyro-Babylonian style.

As it was mentioned the city was ‘cut’ into two parts by the Euphrates. The old and the new city were linked by at least one long bridge. But the two parts had also been linked through drawbridges (closed at night) and ferry vessels. The old city was always somewhat larger than the city on the west bank.

.

[In fact, this article was a synoptic summary of the chapter on Babylon from my new book: Military architecture of the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean world]

.

Periklis Deligiannis

.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

– Oates J., Babylon, London, 1986

– van de Mieroop, M., The Ancient Mesopotamian City. Oxford, 1997.

– Sags H., Everyday life in Babylonian and Assyria, London 1965.

– “Babylon”, Encyclopædia Britannica.

– “Babylon”, Wikipedia.

Aug 25, 2020 @ 18:13:06

I am writing a novel based on the Bible prophet, Daniel. I would like to use your map of New Babylon from this website. Would you be so kind as to grant me permission to use the map in my book? Thank you.

Terry Thompson

terry@terrythompson.org.

Sep 06, 2020 @ 00:50:27

Terry,

the copyright of the map is not mine or of my website. It belongs to the original source. But thanks for asking anyway.