Republication from heritagedaily

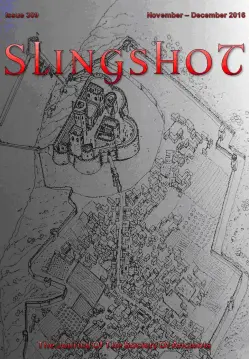

A hill fort is a type of earthworks used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement

A hill fort is a type of earthworks used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage.

The fortification usually follows the contours of a hill, consisting of one or more lines of earthworks, with stockades or defensive walls, and external ditches. Hill forts developed in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age, roughly the start of the first millennium BC, and were in use by the ancient Britons until the Roman conquest. There are around 3,300 structures that can be classed as hillforts or similar “defended enclosures” within Britain, all worthy of considering. The following list represents ten of the most impressive examples.

1 : Maiden Castle, Dorset

Maiden Castle is an Iron Age hill fort 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) south west of Dorchester, in the English county of Dorset. The name Maiden Castle may be a modern construction meaning that the hill fort looks impregnable, or it could derive from the British Celtic mai-dun, meaning a “great hill.”

The earliest archaeological evidence of human activity on the site consists of a Neolithic causeway enclosure and bank barrow. In about 1800 BC, during the Bronze Age, the site was used for growing crops before being abandoned. Maiden Castle itself was built in about 600 BC; the early phase was a simple and unremarkable site, similar to many other hill forts in Britain and covering 6.4 hectares (16 acres). Around 450 BC it underwent major expansion, during which the enclosed area was nearly tripled in size to 19 ha (47 acres), making it the largest hill fort in Britain and by some definitions the largest in Europe

Image Credit : Google Earth